Whenever I argue that morality is subjective I encounter people who regard that idea as so unpalatable that they are determined that we must find a scheme — somehow, anyhow — in which morality can be regarded as objective. The term “subjective” has such negative connotations. I argue here that such connotations are not justified.

If we ask what morality actually is, the only plausible answer is that morality is about the feelings that humans have about how we act, particularly about how we treat each other. This was proposed by the greatest ever scientist, Charles Darwin, who in Chapter 3 of his Descent of Man stated that that “moral faculties of man have been gradually evolved” and added that “the moral sense is fundamentally identical with the social instincts”.

He explains that in social animals such instincts would take the form that in each individual:

… an inward monitor would tell the animal that it would have been better to have followed the one impulse rather than the other.

The world’s greatest philosopher, David Hume, had earlier arrived at the same conclusion. In his An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals Hume explained that “morality is determined by sentiment”, saying that “in moral deliberations” the “approbation or blame … cannot be the work of the judgement”, but is instead “an active feeling or sentiment”.

Hume continues:

In these sentiments then, not in a discovery of relations of any kind, do all moral determinations consist. . . .

… we must at last acknowledge, that the crime or immorality is no particular fact or relation, which can be the object of the understanding, but arises entirely from the sentiment of disapprobation, which, by the structure of human nature, we unavoidably feel on the apprehension of barbarity or treachery.

No-one has ever suggested any alternative account of morals that makes the slightest sense. The main alternative suggestion is that morality is about the values and feelings of gods, rather than of humans, but we have neither hide nor hair of any gods, whereas we know that humans exist and have evolved.

Given our evolutionary past, in a highly social and cooperative ecological niche, we will inevitably have been programmed with moral feelings, feelings about how we act towards each other. Thus morals are rooted in human values and in what we like and dislike. That makes morals, at root, subjective, since the term “subjective” means “based on or influenced by personal feelings, values and opinions”.

Whether an act is regarded as “morally good” or “morally bad” must, in the end, be a statement about how humans feel about the matter. No viable alternative has ever been proposed.

But that makes many people unhappy! They want objective status for moral judgements; effectively they want objective backing for what they themselves feel to be morally right.

The most common tactic to try to achieve that is based on the entirely correct idea that one can make objective statements about subjective issues. Thus, Tom’s liking for chocolate ice cream is subjective, but, given that, the statement “Tom likes chocolate ice cream” is objectively true.

In a similar way, one can set up a moral framework by declaring axioms such as “the moral thing to do is to maximise the well-being of sentient creatures”. Given that axiom, it would then be objectively true that, for example, torturing children for no purpose would be immoral. Excellent! People really do feel that torturing children for no purpose must be objectively immoral, that is, immoral in some way beyond “mere” human feelings.

But this approach doesn’t get you an objective scheme, despite how superficially appealing it might be. First, whence that axiom? Unless you can derive that axiom from first principles (which no-one ever has), you are simply declaring it as your moral opinion. Which makes the framework merely a report of your own subjective values. The only normative standing that such a framework has is through your advocacy, or that of other humans, and that suffices to make the scheme just as subjective as anything else.

Second, any notion of “well-being” depends entirely on what people like and dislike, even if it is as basic as the human preference for being alive and healthy over being diseased or dead. All this axiom achieves is placing the subjective element at one remove, sufficiently far that people can fool themselves that they’re on the track to a truly objective morality.

So why are people so unwilling to accept the — surely? — blatantly obvious truth that morals are all about human feelings and values, and thus are subjective? I consider that it results from several misconceptions about what morality being “subjective” entails.

Subjective does not mean unimportant!

Saying that morals are “subjective” does not imply that they are unimportant and disposable, in contrast to “objective” morals which would necessarily matter.

In fact, the truth is the opposite. Subjective morals are all about our “values, feelings and opinions”, in other words about the things that matter to us — indeed, our feelings are the only things that actually matter to us! There is nothing second-rate about a subjective moral scheme: such a scheme founds morals in our very nature and our deepest feelings and values.

In contrast, if morals were “objective” then they could be entirely unrelated to what matters to us. For example, suppose that some god had decreed, in his wisdom, that it was “morally wrong” to wear a garment made from more than one sort of thread. That would be a morality that was unimportant, since we couldn’t care less; there is no good argument from human values for such a prohibition, and so such a “morality” would be entirely disposable.

Subjective does not mean arbitrary!

Nor does a subjective moral scheme amount to an arbitrary one. Human feelings and indeed human nature are not arbitrary. Indeed, much of our basic human nature derives from evolutionary programming, about which we have no choice. We can’t just decide to feel good about watching a child being tortured for no reason.

In contrast, it is the supposed “objective” rules, the ones that would be, by definition, unrelated to human values and human nature — the rules such as the prohibition on wearing garments of mixed thread — for which there are no good reasons, and which are thus arbitrary.

Subjective does not mean that one person’s values are no better than anyone else’s!

“So you are saying that one person’s morality is just as good as anyone else’s; Ghandi’s morality is no better than that of a sadistic mass murderer!” is the aghast complaint.

This complaint presumes that, if morals were subjective, then we would be unable to rank different people’s ethics. But we can indeed do so, simply by using our own evaluation of their merits. Most people would rate Ghandi’s morality above that of Stalin. What we can’t do is rank them objectively — that means, rank them without any reference to any human judgement on the matter.

The phrase “one person’s opinion is as good as another’s” implies that we can indeed rank the two objectively, and that the two have exactly the same rating. But that is exactly what subjective morality is not doing. There is no such thing as an objective ranking scheme, and thus it is not true that “one person’s opinion is as good as another’s”. Indeed, given that there is no objective standard of morality, that phrase is effectively meaningless.

One can, of course, ask people to rank different ideas, based on their values, and if one did that one would not find that everyone ranked equally. Indeed, most people have no difficulty at all in judging some people as moral exemplars and others as morally bad.

Subjective does not mean that you can’t tell someone else that they’re wrong!

“But if morality is subjective, then you can’t tell someone else that they’re wrong to lie or cheat or steal!!”

Oh yes you can, that is exactly what you can do. You are wrong to lie, cheat or steal. See, I just did! It is very easy to offer ones opinions on other people’s conduct, and indeed many of us are rather free with such opinions. Much of politics consists of people opining on the morality of the government’s policies, or those of opposing parties.

What you cannot do is claim objective backing behind your opinion. And people really dislike that; they really like to feel that their opinions are not “merely” their opinions but that they reflect some objective property of the world. Well tough; the fact that you might want objective backing for what you regard as fair or just or moral doesn’t mean that the world is like that.

No moral philosopher has ever produced a coherent account of what objective notions of fairness or justice or morality (notions that would have to be entirely independent of human judgements) would even mean.

As a basic empirical fact, the world is full of people who have opinions about what is just, fair or moral, but there is a rather striking absence of any other form of justice, fairness or morality.

People try to influence society about these things, and societies make collective agreements about them. But, that’s it; people and their opinions and their values is all there is. There is nothing more to morality than that. There is no objective property of nature, no property akin to electric charge or gravitational mass, that determines what is moral. People can try to invoke gods to back up and embody their opinion as to what is moral, but such gods don’t actually exist.

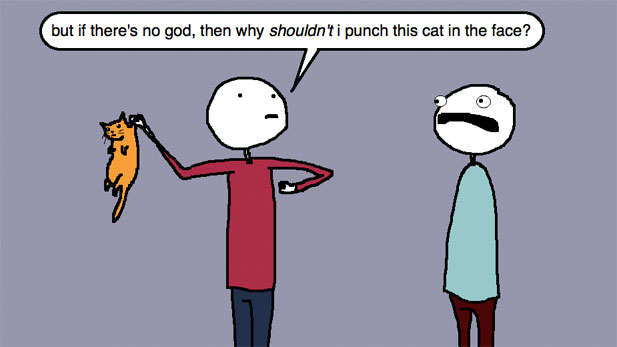

Because the guy on the right will dislike it (and so might you). [You might want a better reason than that, but that doesn’t mean that there is one.]

But whence the justification, the normativity?

At this point, those hankering after objective morality get really unhappy. If morality is “merely” about human opinion, whence the imperative behind it, whence the normativity?

Well, other than human feelings, there isn’t any. Sorry, but there isn’t. Morality really is about human feelings (including your own) about how humans treat each other. De facto, if you do something that other humans regard as heinous, then they might punish you; and you might also feel bad about it. But the gods won’t care, because there are no gods to care; and the rocks and trees and the clouds won’t care, because they are not the sort of things that care.

It is a fundamental misreading of nature to suppose that nature is moral. The physical universe is amoral, literally incapable of caring about morals. Darwinian evolution is amoral, being a blind and unfeeling process that is equally incapable of caring. But some products of Darwinian evolution — sentient beings that have evolved into social and cooperative ways of life — do care about how they interact with other members of their species.

The fact that we humans care is the source of moral imperativity, the only source and indeed the only meaning of moral imperativity.

But those hankering after objective morals don’t give up. If — as above — they declare their moral axioms and develop their moral frameworks, then surely we then have objective moral imperatives and thus objective normativity following from those axioms?

It doesn’t work. “The moral thing to do is to maximise the well-being of sentient creatures” says the axiom. OK, but then why are we obligated to maximise the well-being of sentient creatures? Because it’s the moral thing to do!

But what do you mean by “the moral thing to do”? By the axiom, it means only the thing that maximises the well-being of sentient creatures. So, the claim amounts to: we should maximise the well-being of sentient creatures because it will maximise the well-being of sentient creatures.

This doesn’t give normative force, it gives only a tautology. One could regard “moral” as a mere label for things that tend to maximise well-being, but a label doesn’t give normativity. Any attempt to extract normativity just results in a tautology or a declaration by fiat. Why should we do “the moral thing”? Someone’s feeling that you should do it really is the only normative force that there is.

If someone rejects your axioms and your moral framework, what is your recourse? Your only recourse is to appeal to values — either theirs or yours — and seek to persuade them based on their humanity and their values. That is the only basis for normativity.

Accepting that morality is subjective is counter-intuitive. Most humans feel intuitively that there must be some objective basis behind it. But, when examined, no attempt at making morality objective actually works. Subjective morality is all there is; but, also, it’s all we really need.

By this reasoning, all is permissible, right?

It depends what you mean by “all is permissible”.

If you’re asking whether there is a Sky Daddy with a big stick who sees everything and will punish you for certain acts, then the evidence is that no there isn’t.

If you’re asking whether there are humans who might punish you for certain acts, then the evidence is that yes, there are!

If you’re asking something else, please clarify.

There is no objective right or wrong?

Correct, there is no objective right or wrong. Indeed no-one has ever made a sensible proposal of what “objective right or wrong” (that is, right or wrong independent of everyone’s opinion) would even mean.

No, all is not permisslible. Don’t you know that if you touch yourself, you’ll go blind?

Of course, there is a necessary supervenience of moral on physical facts.

Haven’t you seen the soul-o-meter at work, predicting the fate of the newly dead by measuring the weight of misdeeds weighing down their spirits?

That is the nature of the situation which an ‘objective morality’ (not just moral realism) proposes.

Permissibility, otherwise requires an arbiter with a point of view and intentional motives – a subject.

Here me out guys,

Coel, could it be that your argument is based on a set of assumptions which have been said over and over again such that they have apparently solidified into “facts”

I’m familiar with the argument of moral subjectivity and it’s just sereocomical how in these discussions it always seems to be one man’s opinion gone viral.

I asked a simple question and Coel flew off with details denouncing the existence of God. It think that’s the real argument. Just so you know; the existence of God is one of the most empirically verifiable truths, although it’s the most intellectually resisted.

Putting that aside; Darwin is the “greatest scientist” ever? And that supposedly “greatest”philosopher, what was his name again? My point is that you really went overboard with the issue Coel.

The holocaust was objectively wrong, and this is empirically verifiable.

I hope you’ll continue to do your research with a humble heart, and in the understanding that the mind is quite credulous and elastic. Consider how the arguments for and against the Flat Earth? The honest assessment would be that it’s easy to bounce between two contradicting opinions.

Someone once said,

There is a hell of a difference between wise-cracking and wit;

Wit has got truth in it, but wise cracking is simply calisthenics with words.

Then feel free to empirically verify it!

Then feel free to empirically verify it!

very well put and I for one entirely agree morality can only be subjective

Hello Coel, how are you doing?

I’m not sure if we disagree or are in violent agreement here:

Well, quoting Darwin you make a good case for a first approximation of morality. But isn’t that equivalent to saying ‘the well-being of conscious creatures?’ If that is what we mean when we say morality, would the moral thing to do to be the thing that maximises that?

I’m saying it come from how we defined the words.

Like how we have defined health a certain way. Thus, it naturally follows that a healthy action is one that maximises healthy. Broccoli, generally speaking, would be a healthier choice than chocolate. (Usually.) While chocolate is not likely the healthiest solution, if you are healthy it’s not really unhealthy to eat a small amount of it.

So, I can agree that there are objective facts about something subjective like morality. (Even though that’s not how philosophers and theologians use the term subjective.) And that morality is based on our biological facts (i.e., our evolution).

But it directly follows from these ideas that maximising wellbeing is the moral thing to do. Because wellbeing is defined by our biological facts (including both nature (genetic) and nurture (development/psychological)).

I don’t think we can escape it. Can you meet me there if I can meet you at not calling this objective?

Hi Shawn,

The central issue here is what “the moral thing to do” actually means and whence moral imperativity. If you are saying something along the lines of “maximising wellbeing is what is most in accord with my feelings and values”, and thus is what *you* want people to do, then I fully understand your position.

If, however, you are conceiving of “the moral thing to do” in some way that isn’t a report of someone’s preferences, feelings and values, then I — quite literally — don’t understand what you mean.

Okay, I think I more fully understand your objection here. Please for the sake of debate grant that the moral thing to do is to maximise the well-being of conscious creatures.

Given that, your issue seems to be there is no reason to do that (no imperative to act moral given that definition of morality).

I agree. Just like there is no imperative to do the healthy thing. But that is irrelevant to me. It is the moral thing to do and if people choose not to care about morality that’s on them. If people have some other goal they can have it. But other goals are clearly not what is meant by morality, as I believe you demonstrated in the above blog post.

I’m willing to grant it, but I’m not sure that I know what it’s supposed to mean. Are you suggesting that “the moral thing” is a label that we choose to apply to “maximising the well-being of conscious creatures”? (If not, please explain what you mean.)

If so, then, yes, I can grant it in the same way that I can choose to apply the label “the twyntot thing” to “maximising the well-being of conscious creatures”.

Yes, in the same way that it is the twyntot thing to do. And if people don’t care about twyntotness then ok. I’m not sure what this labeling achieves.

Yeah, but “maximising the well-being of conscious creatures” is NOT what people mean by morality either! For example, people usually care far more about their own children than random, unrelated conscious creatures. If a man cared no more for his own children than he did for a kangaroo in Australia or a yak in Tibet, then people would *not* regard that person as “moral”, they’d regard him has a grossly immoral man who neglected his children.

I’m sorry, I must disagree with your dismissive example.

You are saying that an environmentalist who lobbies all levels of their government to enact stricter environmentalist laws and regulations doesn’t care about protecting the earth’s environment… because they aren’t lobbying in another country?

Or are you saying that my friends who go to science fiction conventions, pay a lot of money to take pictures with the actors, and watch way too much Star Trek are NOT Star Trek fans because they don’t like all the characters on the show equally?

These analogies are being used to highlight one flaw in your dismissive counter example. That because you are doing one thing (the thing that is within your ability and reach) doesn’t imply you don’t value another. And the fact that you personally value one thing more than another doesn’t mean that you are acting in accordance to your ideal. And further, remember that people who do the moral thing aren’t usually doing what they subjectively want.

But more to the point: morality is based on the idea of helping people thrive. It’s more of a test we apply our decisions to in order to see if a decisions is moral. How does it stack up compared to the alternatives. That’s how we use the moral sense. The fact that we are mainly dealing with those near us is an issue of geography, not so much morality.

It almost sounds like you are saying people are doing what they want. That’s not the case. People understand that what they want and desire is different from what is moral. I think that kind of torpedoes the last bit of that comment.

Also, I think you previous point called all communication arbitrary and inane. Of course we decide what combination of phonemes mean what. That’s all language is! Morality is a label we are applying to a part of our humanity. You tried to explain it, and I feel like I’m mostly agreeing with you. But you clearly do not. And, you seem to think that language is stupid.

No, I am not saying that at all, or anything like that. But the point is that if anyone wants to argue for an **objective** moral scheme based on “maximising well-being of sentient creatures” then, in order to have a maximising function, you need an *objective* means of weighting different sentient creatures. What is your scheme? My point is that “everyone counts equally” does *not* accord with what most people would regard as “moral”.

No, people’s feelings about “what is moral” are just part of the package of feelings about what people want and desire.

No, I didn’t.

No, I do not.

I pretty much agree with all you said. I still wonder why play the moralist game.

When we see humans living in a certain way, or they refrain from torturing and eating babies, what do we gain by putting our descriptions in moral language? Other than perhaps you fit in well at the pub or at the town hall.

A baby that is not killed will, for starters, not be killed, but it will also go on to be a toddler. Individuals and societies have many reasons why they want this. A full description of the different options and the different outcomes seems to exhaust what we as reflective beings want to engage in. Adding that we have now chosen the moral thing, either subjectively or objectively, adds little information.

Coel, as you might guess, we disagree mightily.

You correctly say “But some products of Darwinian evolution — sentient beings that have evolved into social and cooperative ways of life — do care about how they interact with other members of their species.”

Yes, we care about how we interact with other members of our species. Why? We care because our ancestors who did not were poor cooperators and tended to die out. That is also why we have a moral sense and cultural moral codes. So why are you looking only at the proximate source of moral behavior – motivation from our moral sense? It is much more culturally useful to draw conclusions about morality from its ultimate source, cooperation strategies, which have been encoded in our moral sense and moral codes.

The big problem with your approach is that people’s moral senses motivate behaviors that are diverse, contradictory, and bizarre. This diversity makes them essentially culturally useless for resolving moral disputes. What cultural use do you see for your subjective brand of morality if it cannot be used to resolve moral disputes?

I also was surprised to see you say: “No viable alternative has ever been proposed (to this subjective morality)”. Surprised because I remember you previously agreeing that the objective function of morality (as a category defined by our moral sense and cultural moral codes) is something like “to increase the benefits of cooperation in groups” (as is confirmed by the science of the last 40 years or so).

Further, the normal methods of science identify a self-consistent subset of these cooperation strategies that appear to define an objective, universal function of morality: “to increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity (think the Golden Rule).” That universal function of morality defines a culturally useful universal reference for resolving moral disputes. If your moral sense tells you that doing something that is likely to, on average, decrease the benefits of cooperation, you are objectively wrong. If your moral sense tells you that a cooperation strategy such as slavery which violates the Golden Rule is moral, you are objectively wrong.

By what criteria do you argue that this objective cooperation morality is not a viable alternative to your subjective, emotion based morality?

Sure, science is silent on the goals of moral behavior (though most groups will pick their favorite version of increasing well-being) and cooperation strategies can be implemented in myriad ways – so some implementation aspects of cultural moral codes will differ and be subjective. But knowing the universal function of moral behavior remains a powerful tool for resolving moral disputes. If nothing else, it clarifies what about morality is objective and what is subjective.

At least we agree there is no objectivity about morality’s bindingness regardless of our needs, preferences, and moral sense. There is that, anyway.

Hi Mark,

Indeed, and the post was written partially with you in mind!

Because that is the only source of moral normativity. Evolution is an a-moral process. Evolution literally does not care, it is incapable of caring. But, evolution produces beings that do care. It is their caring that morality is about and that is the only source of moral normativity.

It is useful in that it properly understands morality and thus disposes of wrong and misleading ideas. You are right that it does not supply an algorithm for settling moral disputes — the request for one is misconceived.

Yes, that is an objectively true statement about the function of morality and why evolution has programmed us with moral feelings. But no normative imperative follows from that! Evolution is an a-moral process, it does not do moral imperatives. Thus no moral imperatives follow from understanding evolution.

Whence the normativity? Evolution does not issue moral imperatives! So are you offering *your* opinion? If so, fine, but if it is your opinion then that makes your scheme subjective.

What do you mean by “is moral” as used there?

Because the only basis for this “objective cooperation morality” is your advocacy of it (or that of other humans)! Thus it is not “objective”! That holds unless you want to argue that evolution itself is a moral agent that issues imperatives.

Understanding humans and understanding evolution can indeed helpfully *inform* our moral discussions. But evolution can not supply the normativity.

Human beings are more or less objectively determined. So is their morality.

Human beings come from a given genetic, epigenetic, and other inherited characteristics (“phenotype”). Call that a hardware. Given that hardware, some natural operating systems arise. The most fundamental of these can be called “instincts”.

The hardware has to do with these subjects: it define them. Thus those “subjects” are actually “objects”.

As the “subjective morality” is intrinsic to subjects who are actually objects, why to bother making distinctions between subject and object?

Hence human ethology is objective in that sense. The same reasoning is pertinent, even more so for any animal species. This is why any species come with a well defined ethology, characteristic to that species (supposing the notion of species is well defined… it’s not).

Human ethology is ground zero for human morality. That ground is a logic which is both complete and non-contradictory (so it’s much better than all metamatematics except trivial examples). Morality can force human ethology, but cannot deny it.

Human ethology, thus human basic morality is humane. At the very least in the sense that it makes the human species possible.

Human beings do not just care about how they interact with other people. They care about how they interact with themselves. They come equipped naturally with software, such as remorse, or disgust with bad faith, which make them caring about being caring and mentally correct.

That was just an example. Both traits just quoted have to do with the fact human beings are truth machines. Upon truth, well-being, or just survival of human beings depend. So the search for truth is a strong instinct (not just restricted to scientists!) A human brought up by wolves in a cave would have it.

We don’t need to look for a god outside and above. It comes naturally within.

Yes! A thousand times yes. A marching band replete with confetti and majorettes of yes.

In the same way the religious use god as the source of their authority, some secular moralists try to imbue the idea of objectivity as an unchanging, impartial arbiter of right and wrong. [If I had a penny for every time I hear someone say “(fill in the blank) is objectively wrong no matter what”.] We want these sources of authority as they make us feel secure. We rely on those convictions to end the discussion sometimes, at the detriment of progress. We place ourselves at a logical disadvantage to the religious when we try and use their rationalizations of authority. Embrace moral relativism. The sooner you get used to it, the better.

The uncomfortable truth is, of the 10 people in a room, no one of them will view morality in exactly the same way. It’s the nature of subjectivity.

Thanks Coel, for an outstanding article.

Hi Coel,

I understand you are using an un-useful, but unfortunately too common, definition of normative – something like objectively binding regardless of our needs, preferences, and moral sense. As we have discussed before, I argue Gert’s definition (see SEP’s “Morality” entry) based on universality is far more useful. Paraphrasing, normative refers to “the moral code that would be put forward by all well-informed, rational people”. Gert’s definition is more useful because it refers to something that has a chance of being real and culturally useful.

Because I knew that we disagree about its definition, I intentionally did not use the word “normative”. My discussion of the greater cultural usefulness of cooperation morality is based only in its ability to resolve moral disputes due to it defining what is universally moral. Your subjective morality seems incapable of resolving moral disputes.

Do you think the ability to resolve many moral disputes is not culturally useful?

Perhaps the moral code put forward by all well informed, rational people is not useful for resolving moral disputes?

Or perhaps well-informed, rational people would not put forward a moral code based on the principle “behaviors that increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity (think Golden Rule) are universally moral”?

Hi Mark,

The problem with that is that knowledge and rationality are not sufficient for a moral code: you also need values, aims and desires. A computer program could, for example, by highly informed and supremely rational, and yet entirely unfeeling and a-moral.

So, perhaps you mean something like “the moral code that would be out forward by all well-informed, rational people, and assuming typical human nature and typical human values, aims and desires”.

The problem with that is, first, that since it depends on human values and feelings, it is subjective (by the every definition of the word). Universal is not the same as “objective”. If all humans liked chocolate, that liking would still be “subjective”.

Second, being universal to humans would not make it universal. Humans have a particular human nature owing to our evolutionary history. Species with very different biologies, such as the social insects, would have very different natures and thus would produce very different moral systems.

Third, “human nature” is not the same across all humans. That’s because we all have slightly different genes, and thus genetic programming, and also because we’ve all had different upbringings and environments, and thus have differences in our natures, temperaments and personalities. That’s why people who are well-informed, intelligent and rational can disagree about politics — they have different values.

There is no sensible basis for supposing that there is one “right” answer that can be applied “universally” to humans such that we all agree it is best. Given our differing personalities, there will inevitably be a spread of opinion.

For all the above reasons, your scheme does not produce an “objective” morality, nor a “universal” one. It’s a good attempt, but a flawed one. Basically it derives from the idea that the word “subjective” must be avoided at all costs, and that we must thus cast around for some way of getting to apply the label “objective”.

I think we should, instead, accept that, whether we like it or not, human morality is subjective, and then proceed from there.

I think that schemes that FALSELY claim objective morality and objective ways of settling moral disputes are very dangerous, because people can think they give permission and indeed a duty to impose them whatever the costs. If you look at communist ideology or National Socialist ideology or similar they are all what their proponents regarded as highly moral schemes, schemes that people felt they had a moral duty to impose, coupled with the idea that anyone opposing them must be immoral and wicked.

There is a lot to be said for the humility of recognising that ones moral schemes and ideas really are just ones own opinions; they are not objective facts that morally override the views of others.

I don’t think there can ever be a straightforward algorithmic way of adjudicating moral disputes (human beings will always have competing ideas and values), and I think it is dangerous to suppose that there is.

You are right! Plenty of well-informed, intelligent and reasonably rational people do not put forward that moral principle! But then, of course, no human is perfectly rational and entirely devoid of all feelings and values. And such a person would not, in any case, have a conception of morality, since they’d have no feelings and values. So, sorry, but I don’t think your starting points for your moral scheme are viable!

Coel said: So, perhaps you mean something like “the moral code that would be put forward by all well-informed, rational people, and assuming typical human nature and typical human values, aims and desires”.

No, that is not what I mean at all. Cooperation morality defines morality’s universal function (increasing the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity). This function is just a special subcategory of cooperation strategies; it’s just mathematics.

Innate goals or values are no more a part of these strategies than innate goals or values are part of any other mathematics.

On the other hand, whether one thinks one ‘ought’ to act consistently with it, what the goals of this cooperation ‘ought’ to be, and the particular way these cooperation strategies are implemented do depend on subjective “values, aims and desires”.

Perhaps I am not clearly communicating the sharp demarcation between 1) what science tells us the universal function of morality objectively ‘is’ and 2) the completely separable role of subjective “values, aims and desires” in determining if we ‘ought’ to adhere to the implied moral system, what its goals ‘ought’ to be, and the specifics of how it is implemented.

Coel said: Plenty of well-informed, intelligent and reasonably rational people do not put forward that moral principle! But then, of course, no human is perfectly rational and entirely devoid of all feelings and values. And such a person would not, in any case, have a conception of morality, since they’d have no feelings and values. So, sorry, but I don’t think your starting points for your moral scheme are viable!

Consider the following syllogism:

1. The universal function of morality is to increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity.

2. If premise 1 is true, then all rational people can be convinced it is true.

If premises 1 and 2 are true, all well-informed rational people will put forward as a universal moral principle that behaviors that increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity are moral.

The opinions of people who are not well informed (here about the science done on cooperation and morality in the last 40 years or so) or who are not thinking rationally are irrelevant to Gert’s definition of normative. Normativity does not require everyone to agree, just the hypothetical well-informed, rational people with different “values, aims and desires” to agree. (Gert’s definition of normative does not require anyone to be “devoid of all feelings and values.”)

Implementing and practicing the cooperation morality principle in fact requires people to have “values, aims and desires”. Without “values, aims and desires” there would be no motivation to practice it, no way to choose goals for cooperating, and no way to choose how its strategies will be implemented. The objective component of this morality is its function. The subjective part is its motivation, goals, and specific implementation.

But how can cooperation morality objectively resolve moral disputes if it has a subjective component?

Consider the example “Do to others as you would have them do to you” which for many people summarizes morality.

It is also an excellent heuristic for indirect reciprocity. Does indirect reciprocity innately have any values? No, and, understood as a useful heuristic for a cooperation strategy, “Do to others as you would have them do to you” is also value, aim, and desire independent.

“Do to others as you would have them do to you” can certainly be used as a moral reference to resolve many moral disputes. What may be surprising to many is that it can often do so without any requirement that its motivation and goals be specified.

Coel, we may be making no progress in changing anyone’s position, but our discussion has been useful to me. It had not previously occurred to me that “Do to others as you would have them do to you” can be as value, aim, and desire independent as indirect reciprocity.

Hi Mark,

I don’t understand that at all. I don’t see how one can have a strategy without a goal, since a “strategy” is a plan for attaining a goal.

One can only talk about something’s “function” by reference to some goal that the function attains. The function of morality — from the evolutionary point of view — is indeed to increase cooperation. But human goals are not necessarily evolution’s (metaphorical) goals. Thus the “function” of morality from the point of view of a human is not necessarily the same as the function of morality from the point of view of evolution.

As an illustration, from the evolutionary point of view, the function of sex is furthering the goal of procreation. From the point of view of a human, who might have different goals, the function could be different, for example pleasure.

My difficulty with your scheme is that you switch between the evolutionary point of view and the human point of view. As an example:

I agree with premises 1 and 2. But what does the phrase “… are moral” at the end there actually mean? When most humans use the phrase “this behaviour is moral” they are mostly intending it as a normative statement. But no normative statement follows from your premises 1 and 2.

If the phrase “… are moral” is simply meant to be descriptive, then your sentence amounts to something like: “behaviours that increase cooperation lead to increased cooperation”.

Coel: “Evolution is an a-moral process. Evolution literally does not care, it is incapable of caring. But, evolution produces beings that do care. It is their caring that morality is about and that is the only source of moral normativity… Evolution is an a-moral process, it does not do moral imperatives. Thus no moral imperatives follow from understanding evolution.”

“Moral imperative” is mumbo-jumbo from Kant. This Prussian apparently envisioned morality as a commander who gave order. Kant was also for slavery, from the moral point of view, thus cannot be taken seriously, except if one wants to advocate deviance from ethology. Indeed human beings were not made for slavery (how to you put in chains people when there was no metallurgy?)

Morality is not just about “caring”. Its original definition and invention by the Roman Consul and) philosopher Cicero deliberately duplicated the Greek “Ethikos”. The Greek “ethos” means “habitual character and disposition; moral character; habit, custom; an accustomed place,” in plural, “manners.”

The first thing “habitual character and disposition” enables, in any species, is the survival of the individual. The first and true “Golden Rule” of morality considered in the most basic way, is the survival of the self. So morality is not just about others. Far from it. Morality is anchored in the care of the self. Then the care of the group which allows the self to survive, etc.

Considered that way, Kant’s disposition that slavery was an excellent thing has to do with the care he took of himself. It has to do with Kant’s internal Golden Rule, that his well-being was first. By advocating slavery in the Caribbean, he implicitly supported the quasi-slavery in which his Lord, the King of Prussia, was holding Jews and Poles.

“Evolution” is not a so-called “moral person”, indeed. However, mathematically, that is, in a mentally minimal fashion, evolution can only be defined as the set of all creatures which have ever been, in the last few billion years, chronologically ordered. So evolution, a process can only be defined as a collection of objects, life forms (some of which some who pretend to think “philosophically” call, weirdly enough, “subjects”).

When chains of those living creatures became endowed with “habitual character, or disposition, customs, manners”, they became moral. The distinction between those character, disposition, habits, and “instincts” is impossible. So the ground state of behavior, ethology, the logic of those can’t be distinguished from the work of reason.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: The term “morality” can be used either:

1.descriptively to refer to some codes of conduct put forward by a society or, a) some other group, such as a religion, or b) accepted by an individual for her own behavior or

2.normatively to refer to a code of conduct that, given specified conditions, would be put forward by all rational persons.

“Reason” depends upon generalized ecology, the logic of the house (eco), of the environment. So, widely different ecologies, or variegated circumstances, can, and will, lead to wildly different reasons, hence extremely different moralities. For example, the Aztecs had a protein problem which they solved industrially, and rationally, but quite differently from most civilizations.

Morality is neither absolute, nor relative. It’s definitively quite a bit of both. Morality is a function of genetics, epigenetics, phenotypes, general ecology, history, circumstances, moods and hopes. Given all the latter, morality becomes pretty deterministic. Thus, to change it, we have to act on the latter.

Coel: Well, argued about the morality issue, and I agree completely.

However, it is indeed a curious coincidence that the people you consider to be the world’s greatest scientist and philosopher ever are also British, like yourself. (I have a hunch who you might consider to be the world’s greatest playwright ever.) Now I can’t really give you empirical evidence for why this or that 20th century American physicist, medieval Chinese poet or ancient Indian philosopher would be even greater in their categories because I am insufficiently acquainted with the works of all the world’s greatest. But that’s just the point; unless you have spent the last three hundred years mastering all the world’s languages to be able to read everybody in the original, its history of science, and its history of philosophy, so are you.

Hi Alex,

Well ok, fair point, I maybe am being a little parochial. However, if by “greatest scientist” I was meaning the person who had contributed most to the current scientific understanding that is common across the world, from Europe and the US but also Japan, Russia, India, China, etc, then I think one can make a fair case for Charles Darwin. Since today’s science supersedes local culture, it is reasonable to make such an assessment.

In philosophy I will grant that it is harder to construct a “figure of merit” to evaluate different philosophers, so perhaps by “greatest ever” I mean that Hume is the one that I, personally, consider to have been first to a lot of right answers. 🙂

Coel: “One can only talk about something’s “function” by reference to some goal that the function attains.”

No, that is not true in science. In science, “function” refers to the primary reason something exists. For example, the function of a heart is to pump blood. It makes no sense to say the goal of the heart is to pump blood because a heart has no intention.

The primary reason our moral sense and cultural moral codes exist is that they increased the benefits of cooperation in groups for our ancestors. Therefore, their function is increasing the benefits of cooperation for groups. To say that function necessarily must include defined goals would make no sense. People have behaved and continue to behave morally in order to accomplish a plethora of goals, both proximate and ultimate.

Coel: “As an illustration, from the evolutionary point of view, the function of sex is furthering the goal of procreation. From the point of view of a human, who might have different goals, the function could be different, for example pleasure.

Again no, in science, even in evolutionary science, we can sensibly talk about the primary reasons something exists – but talking about science’s or evolution’s “goals” makes no sense. Sometimes serious scientists do talk about something’s ‘goals’, such as a gene’s goals, but only because it is a convenient manner of speaking; there is no implication of intent and it is understood that what is meant is “the primary reason something exists”. Yes, that can be confusing.

Coel: I agree with premises 1 and 2. But what does the phrase “… are moral” at the end there actually mean? When most humans use the phrase “this behaviour is moral” they are mostly intending it as a normative statement. But no normative statement follows from your premises 1 and 2.

Yes, I mean it as a normative statement. It is normative abased on premises 1 and 2. What all well-informed rational people will put forward as a universal moral principle is a standard definition of normative (see SEP entry on “Morality”). I suppose I could have included normatively moral definition as a premise.

For convenience, here is the syllogism again:

1. The universal function of morality is to increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity.

2. If premise 1 is true, then all rational people can be convinced it is true.

If premises 1 and 2 are true, all well-informed rational people will put forward as a universal moral principle that behaviors that increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity are moral.

Hi Mark,

I must disagree with this. First, I grant that attributing “goals” to evolution is metaphorical, but it is a useful way of thinking, and the term “function” is (in that context) equally metaphorical, and is about “functions” that further evolution’s “goals”.

We agree that the “function” of the heart is to pump blood. That’s because having blood circulate the body is a “goal”, something that the body (metaphorically) “wants”.

We would not say that the function of the heart is to produce swishing sounds — even though, if we were to remove the goal-oriented view of the heart, that would make just as much sense. The only difference is that swishing sounds are not needed by the body, whereas blood circulation is; but that difference requires a goal-oriented stance.

Take another context that has no “intentional” or “goal-oriented” view (not even as metaphors), say the existence of grains of sand on a beach. Even if we had a good and accurate description of the “primary reason” that the sand grains exist, we would not call that reason the “function” of the sand. That’s because the very term “function” only makes sense from a goal-oriented perspective, either an actual one (such as human goals) or a metaphorical one (such as evolution’s “goals”).

As above, I’m sticking to the claim that attribution of “function” can only be done from a goal-oriented perspective. You are right that from the perspective of evolution’s (metaphorical) goals, the “function” of morality is to increase cooperation.

That does not mean that that is the “function” from some other perspective! Suppose I were to modify your above sentences to:

“The primary reason that sex exists is that it led to descendants. Therefore, the function of sex is having children”.

From the perspective of evolution’s (metaphorical) goals that is entirely true. From the perspective, though, of a person who does not want to have children and takes measures to prevent it, the function of sex in their life could be pleasure and company.

I am emphasizing this because I think that your whole scheme makes such an error — sliding between the evolutionary perspective and the human perspective, by supposing that we are obliged to adopt the same goals that evolution (metaphorically) has, and thus must regard things as having the same function as evolution (metaphorically) does.

This, to me, is the whole “getting an ought from an is” non-sequitur that flaws most moral-realist schemes.

That might be standard among those trying to construct an objective reality, but I am denying that this makes any sense. The first half of the sentence is purely descriptive: “… What all well-informed rational people will put forward …”. From that, no normative moral obligation follows.

The whole thing is, to me, a non-sequitur, a leap from an “is” to an “ought”. It effectively says that we are morally obliged to align our goals and desires with evolution’s (metaphorical) goals. Which is blatantly false not least because evolution’s goals really are metaphorical. Evolution really won’t care what we do.

The scheme is akin to saying that, because the “function” of sex is procreation, therefore we are normatively obliged not to use birth control, because that would negate the “function” of the act.

Here is my version of your syllogism:

1) The universal function of sex is to produce children.

2) If premise 1 is true, then all rational people can be convinced it is true.

If premises 1 and 2 are true, all well-informed rational people will put forward the principle that behaviours that lead to more children are normatively required.

Hi Mark. I’m afraid Coel has the right of it. First:

“In science, “function” refers to the primary reason something exists.”

Not really. I don’t know of any formal definition of function across all of science, but it would be more accurate to say that function is a description of how something behaves in relation to a larger system it is part of. Thus, the heart pumps blood in the body. The reason a heart exists depends on the exact sequence of events that produce an individual heart. Generalizing to many hearts, we can talk about evolutionary reasons why the animals we see today have hearts. This is related to the function of course but I think it’s sloppy to conflate the two.

More importantly:

“1. The universal function of morality is to increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity.”

This is far too strong a claim. The moral sense functions to influence our behavior, just as, e.g., physical pain and pleasure do. It’s plausible that one of the major ways it influences us is in the context of group dynamics and that evolutionary pressures have favored certain cooperative strategies. But it does more. A person alone on an island might feel they have acted immorally by, e.g., masturbating. Moreover, our moral sense is just one part of our overall behavioral system and I don’t see any reason to think that only beneficial cooperation strategies would influence it. Our behavior is, at minimum, a product of competing evolutionary pressures for and against cooperation to benefit our genes.

“2. If premise 1 is true, then all rational people can be convinced it is true.”

It’s not, but for the sake of argument let’s suppose ‘the moral sense’ can be defined in such a way that it is objectively that part of our psychology which developed due to the benefits of cooperation. Then this:

“If premises 1 and 2 are true, all well-informed rational people will put forward as a universal moral principle that behaviors that increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity are moral.”

is still invalid. All informed, rational people would agree that the moral sense developed due to the benefits of cooperation. But it doesn’t follow that any given action is therefore ‘moral’. You would have defined the moral sense by its cause; this says nothing about its judgments. For comparison, I could define the visual system as that which increases the benefits of detecting photons of different wavelengths. This does not define any particular object as objectively ‘red’.

You may then go on to define a moral action as one which increases cooperation blah blah blah but you’ve already admitted this has no persuasive force. It’s arbitrary and non-standard. Why not just talk about cooperative actions if that is what you are interested in? Why the need to designate them objectively moral?

Cole: As above, I’m sticking to the claim that attribution of “function” can only be done from a goal-oriented perspective. You are right that from the perspective of evolution’s (metaphorical) goals, the “function” of morality is to increase cooperation.

Cole, as you mentioned, evolution has no goals. Hence, trying to make important conclusions that depend on evolution having goals, in any form, is incoherent.

Perhaps it would help to think of the two components of interest (cooperation strategies and ultimate goals) as ‘means’ and ‘ends’. ‘Means’ and ‘ends’ are separable in the same way that function and goals are separable.

As another alternative, instead of “function”, I could have said “the reason they are evolutionarily stable”. Why an evolutionary adaptation is evolutionarily stable is separable from the goals people use that adaptation to pursue.

In the same way as in the above two alternative ways of describing moral behavior, the objective function of morality (increasing the benefits of cooperation) is separable from whatever subjective ultimate goals people may be using that means to pursue (pleasing god’s, utilitarian goals, or whatever).

Mark: What all well-informed rational people will put forward as a universal principle is a standard definition of normative (see SEP entry on “Morality”).

Cole: That might be standard among those trying to construct an objective reality, but I am denying that this makes any sense. The first half of the sentence is purely descriptive: “… What all well-informed rational people will put forward …”. From that, no normative moral obligation follows.

The SEP’s definition of normative represents, so far as I know, the standard form in mainstream philosophy regardless of one’s position on moral objectivity.

Your definition of normative, which I have not seen you actually specify, seems to be what I refer to as a “magic ought” normativity which I have not found in the SEP’s entries on morality or moral realism. Yours is a useful definition if you want to show that morality is subjective essentially by definition. Yours is useless for understanding how evolutionary insights into the origins and function of moral behavior can be culturally useful.

Coel, ask yourself the question, “Why would all well-informed, rational people with different goals and needs put forth a particular universal moral principle?” They might do so because 1) they were somehow obligated to do so regardless of their needs and goals or 2) that particular universal moral principle was the product of objective science. Much of traditional moral philosophy has focused on trying to prove the reality of the first alternative. I am pointing out there is now a second alternative based on what objective evolutionary science tells us the universal function of morality ‘is’.

In traditional moral philosophy, both the means and ultimate goals of morality have been considered to be ‘oughts’. What is new is that evolutionary science has moved moral ‘means’ over into the ‘is’ category – and no magic oughts were required to do the job. So I am not deriving an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’, evolutionary science is showing than an old ‘ought’ (moral means) is actually an objective ‘is’.

Hi Mark,

But it’s not me who is making an argument based on evolutionary “function” and/or “goals”, it is you who is making that argument based on the evolutionary “function” of morality. I am replying that the “functional” attribution only makes sense from a goal-oriented view, such that we would say that the “function” of a heart is to pump blood, but would not say that its function is to create swishing sounds.

Yes, “means” and “ends” are separable, I agree, but the very concept “means” only makes sense given some goal.

OK, let’s make that substitution and examine your syllogism:

1. The reason that morality is evolutionarily stable is that it increases the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity.

2. If premise 1 is true, then all rational people can be convinced it is true.

If premises 1 and 2 are true, all well-informed rational people will put forward as a universal moral principle that behaviors that increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity are moral.

Nope, sorry, the conclusion there is a blatant non-sequitur.

Second point, purely-nice, cooperation-promoting morality is not evolutionary stable! It it were, then we’d all be purely cooperative and moral people, and yet we’re not. What is evolutionary stable is a *tension* between moral cooperativeness and selfishness. Yes, morality is part of our nature, but so is self-interest and a capacity to break the rules and do wrong if it advantages us. This tension is standard “evolutionarily stable strategy” theory, since the pure cooperativeness that you’re talking about is *not* evolutionarily stable.

Third point: what is evolutionarily advantageous and stable will always be a function of ecological niche. There is thus nothing universal about such a thing, it is purely a contingent product of local circumstances.

But the whole point is that the anti-realists dispute this whole concept of moral normativity, and thus this sort of definition is exactly what is under dispute.

As for my concept of normativity: well moral “normativity” means an obligation to act in a particular way. My stance is that the only source of obligation is the feelings of human beings. That means you are “obliged” to do something or refrain from something only because — and only to the extent that — either yourself or another human being would like or dislike the act.

By the very definition of the word “subjective” that means that any and all moral normativity is subjective. And since this sort of moral obligation is the very centre of morality, that makes morality subjective.

My reply to you is that no amount of referring to the evolutionary function of moral programming places me under any obligation at all. In the same way, pointing to the evolutionary function of sex does not in any way place me under an obligation to have children.

The only reason such people would put forward anything such is if it derived from their feelings and values. (Which, by the way, would make it subjective).

No, sorry, that’s gobbledegook. It’s like saying, the evolutionary function of sex is to have children, therefore we’re obliged to have children. That is a non-sequitur. It does not follow. The fact that the evolutionary function of morality is {whatever}, places no obligations upon us whatsoever. Not the merest smidgeon of one!

Coel,

It appears you and Mark are indirectly having an “ought from an is” debate here – highlighted by your claims of non-sequitur. I’d be curious to hear both of your positions on this point.

As I see it, “oughts” derive from human desires and goals. Thus “Sam ought to do X” is really a short-hand for “Sam desires W and doing X would attain W”. Now that latter statement is a purely descriptive “is” statement. Thus an “ought” statement can be interpreted as an “is” statement about a human desire. But, one cannot attain “ought” statements from any “is” statement that is not about a human desire or goal.

(Such views were, I think, first developed by philosophers from Hume to Philippa Foot.)

If I were to attempt to summarise Mark Sloan’s position, I’d presume it amounts to something like: “evolution programmed us to be cooperative, therefore we are obligated to act cooperatively”. To me that is a non-sequitur since: (1) it does not involve any human desire or goal, and (2) there is no reason why human desires and goals must be aligned with evolution’s (metaphorical) goals.

Edmond, I plan to answer your question after Coel and I clarify what we are disagreeing about – see my response to him below. I know it will likely sound mysterious and perhaps even incoherent, but I can’t resist trying out a new turn of phrase about ‘is’ and ‘ought’ regarding universally moral ‘means’.

We may not know how to derive an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’, but science can show us that what we thought was an ‘ought’ is really an ‘is’.

Hi Coel,

Our discussion seems to be getting lost in the weeds. Perhaps it would help if we could agree on what we are disagreeing about. I’d summarize our disagreement as

1) Is the objectivity of morality’s function (moral ‘means’) separable from morality’s ultimate goals (moral ‘ends’)?

… the “functional” attribution only makes sense from a goal-oriented view.

…“means” and “ends” are separable, I agree, but the very concept “means” only makes sense given some goal.

2) What is the best definition of normativity, the SEP’s or your claim that “the only source of obligation (normativity) is the feelings of human beings”?

The SEP’s definition of normative represents, so far as I know, the standard form in mainstream philosophy regardless of one’s position on moral objectivity.

But the whole point is that the anti-realists dispute this whole concept of moral normativity, and thus this sort of definition is exactly what is under dispute.

My stance is that the only source of obligation is the feelings of human beings. That means you are “obliged” to do something or refrain from something only because — and only to the extent that — either yourself or another human being would like or dislike the act.

3) Do normative claims based on a science based understanding of universally moral means necessarily go from ‘is’ to ‘ought’ without explaining how that was done?

If I were to attempt to summarise Mark Sloan’s position, I’d presume it amounts to something like: “evolution programmed us to be cooperative, therefore we are obligated to act cooperatively”.

Is that about right?

Hi Mark,

Yes, those are some of the things we are arguing about. E.g.:

Except that “morality” does not have goals. Only humans (and other sentient animals) have goals. Evolution has metaphorical goals, but not real ones.

If we’re discussing moral normativity, then surely what we’re discussing are the reasons why we might be obliged to act in a particular way.

I dispute that any scientific description and understanding can ever produce moral obligations and moral “oughts”.

If we were to boil the issue down to one point I’d say it is this: are there reasons why we morally obliged to act in a particular way? My reply is that any such obligations are really references to how humans feel about things, what they like and dislike. Thus “Sue is morally obliged to do X” means that some number of humans will dislike it if Sue does not do X.

I assert that: (1) the above account of moral obligation — since it is rooted in human feelings and values — makes morality subjective, and (2) there are no other sources of moral obligation (and thus there are no objective moral obligations).

Hi Coel,

I’ll rephrase the questions based on your comments.

1) Is the objectivity of moral ‘means’ (such as defined by Kantianism’s rules) separable from the objectivity of moral ‘ends’ (such as defined by Utilitarianism’s ultimate goal)?

Simple Kantianism claims to define objectively moral means, the Categorical Imperatives, and denies there are objectively moral ‘ends’. Simple Utilitarianism claims there is an objectively moral ‘end’, maximizing total happiness, and denies there are objectively moral ‘means’. If Kantianism and Utilitarianism can make objectivity claims for ‘means’ and ‘ends’ separately, then it is highly unlikely there is a necessary logical error in doing so. If they can do so, it seems highly unlikely I am necessarily making a logical error when I claim there are objectively universal moral ‘means’ but ultimate moral ‘ends’ are subjective.

I don’t see that “Only humans (and other sentient animals) have goals” contradicts my distinction between objective moral ‘means’ and objective moral ‘ends’. Perhaps I would be clearer If I focused on describing them as ‘means’ and ‘ends’ rather than ‘function’ and ‘goal’? (None of these terms are perfect fits for what is being referred to – no surprise there.)

2) What is the best way to understand normativity, the SEP’s definition based on universality or your view that any normativity claim requires justifying why we might be obliged to act in a certain way regardless of our needs and preferences?

3) If we use the SEP’s definition of normativity based on universality (among well-informed, rational people) and science tells us what universally moral ‘means’ are, can science not objectively define what normatively moral means are (an ‘is’ category claim) without making any claims about what we are obligated to do regardless of our needs and preferences (an ‘ought’ category claim)?

I know you do not agree with the SEP’s definition which I understand is widely accepted among philosophers. This is a hypothetical question. The reason I am asking the question is that it is central to what I see as new approach to showing why moral subjectivity regarding moral ‘means’ is false.

Hi Mark,

This is a tricky one for me to answer, since the question is phrased in terms of moral-realist concepts that I don’t accept. But, for the sake of argument, I agree that, in principle, it is possible to separate the objectivity of moral “means” from that of moral “ends”.

It seems that the word “normativity” is causing a hang-up here, so I suggest we just bypass the word for now. What I am interested in, when it comes to morals, is whether and why we might be obligated to act in a certain way, and what the source of that obligation is.

Again, this is tricky for me to answer since it assumes concepts that I don’t agree with. But:

It seems that you (and maybe SEP) are using the term “normative” to mean “universal”. If it were the case that “everyone” put forward the same moral scheme, then science could indeed describe that scheme.

Coel,

Sounds good.

As you say, much of our disagreement is related to the objective reality of moral obligations. We are also disagreeing about moral obligation’s most sensible role in claims about whether morality is objective or subjective.

But wouldn’t it clarify the issues if we separately consider the objective reality of moral obligations and the objective reality of moral claims with truth value?

Assume we agree that, as a matter of science, there are universal moral ‘means’ (such as the cooperation morality principle). Then these universal moral ‘means’ are objective, not subjective, and provide a mind-independent reference for determining the truth value of claims about moral ‘means’.

The objectivity of moral obligations is then a separable issue, right?

Hi Mark,

Yes, ok.

I’m interpreting you as saying: it is objectively true that morality evolved to increase cooperation, and it is objectively true that morality does increase cooperation (and science tells us both of those things). If that’s what you mean, then yes I agree with you.

Hi all,

I have somewhat similar views to Coel’s. But I think the central point can be made more clearly by talking about the truth (or lack of it) of moral propositions. To be clear, the kind of propositions I’m talking about are those like “Action X is morally wrong” and “You have a moral obligation to do Y”. There are other moral-ish propositions that are somewhat unclear or ambiguous as to whether they should be considered “moral”. For simplicity, I’m sticking to the most unambiguously moral propositions.

With that in mind, I would express my position simply by saying that moral propositions cannot be true. Or, to put it another way, there are no moral facts. In saying this, I have no need for the words “objective” and “subjective”, which I find unnecessarily confusing.

Coel sometimes seems to be taking a non-cognitivist or expressivist view, interpreting moral utterances as nothing more than expressions of approval or disapproval (e.g. of actions). My view is more like moral error theory, and I used to call myself a moral error theorist, though eventually I dropped that term. No doubt moral utterances typically do express approval or disapproval, at least when they are made on the speaker’s own behalf. But they are also typically assertions of fact. And I think non-cognitivists are mistaken if they deny this assertoric role.

Hi Richard,

I think I agree with you here. Would the following be a fair summary?:

* There are no moral facts of the form “Action X is morally wrong”.

* Such statements are, in essence, declarations of the speaker’s disapproval.

* Such speakers often regard such declarations as being about moral facts; however, they are making an error in supposing that.

The reason that I often emphasise the subjective nature of morality is that morality itself is certainly real, in the sense that humans have very real feelings that we label “morals”. If we want to understand morality (and persuade people) then saying that there are no moral facts is only halfway there, we then need to give an account of the feelings about morals that people do have.

(PS I’ve been busy with work, but I will get round to the article you sent … eventually!)

Cole,

Sounds like we are good on the subject of clarifying “the issues if we separately consider the objective reality of moral obligations and the objective reality of moral claims with truth value.”

But the key aspect of the cooperation morality principle “Behaviors that increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity (think Golden Rule) are moral” is its science based universality (objectivity) among well-informed, rational people. If it is universally moral, it is an objective reference for determining the truth value of the morality of many claims about morality.

For example any moral claim that contradicts the cooperation morality principle such as “it is immoral to lie to the murderer looking for his victim” (as simple Kantianism might imply) is factually wrong. Also, the claim we are morally obligated to accept a large loss that provides a tiny benefit to many people (as simple Utilitarianism might imply) is factually wrong.

Due to its universality, the cooperation morality principle provides an objective reference for determining the truth value of the morality of many claims about morality. So many moral claims are objectively true or false.

And, as I think we agreed, the objectivity reality of its moral obligation is a separate subject.

Hi Mark,

This gets to the heart of our discussion, in that I simply don’t understand what you’re claiming. When you say: “Behaviors that increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity (think Golden Rule) are moral”, what do you mean by “… are moral”? Since the whole discussion here is about the very basics of morality, you can’t assume that we know or agree on what “X is moral” actually means.

When I’ve asked you this before, you’ve said that “moral” is a label used for things that increase cooperation. But that then makes the above principle an empty tautology.

What else might you be meaning by that “… are moral”? You might, perhaps, mean “… are things that we are obligated to do”, but if that’s what you mean then you need to explain whence the obligation.

Or, by “… are moral”, you might mean “are things that I, the speaker, would prefer that you did”. Is that what you mean?

If not, can you explain?

Richard,

I agree “… the central point can be made more clearly by talking about the truth (or lack of it) of moral propositions where the central point is if there is an objective (universal) basis for morality. You can read my above comment to Cole which includes two examples of objectively false moral claims.

Where a lot of confusion comes from is in how the category of ‘moral’ behaviors is defined.

Following the lead of many moral philosophers, we might say “moral behavior is what you ought to do to live a good life” (virtue ethicists) or “moral behaviors are what we are obligated to do regardless of our needs and preferences” (Kantianism and Utilitarianism). With either of these definitions, it is easy to argue morality must be subjective (has no truth value).

But science deals in data sets of natural facts and the hypotheses that explain them. The data set of descriptively moral behaviors are all behaviors motivated by our moral sense or advocated by past and present moral codes. And the hypothesis that explains this data set is “Behaviors that increased the benefits of cooperation in groups are descriptively moral.” Understanding what is merely descriptively moral it not worth much on its own, but it is an important stepping stone.

With this understanding of what is descriptively moral, we can look for the subset of all descriptively moral behaviors that are universally moral (moral by all societies) and, not coincidentally, self-consistent. That universally moral principle is “Behaviors that increase the benefits of cooperation consistent with indirect reciprocity (think Golden Rule) are universally moral.” And if the principle is universally moral it can be used to judge the truth of many moral claims. (It cannot judge the truth of moral claims about ultimate moral ‘ends’ because the principle is about moral ‘means’, not moral ‘ends’.)

Hi Coel and Mark,

I can see now that my comment wasn’t as clear as I thought it was. Isn’t that always the way with philosophy?

There is, of course, a great deal that could be said about what moral values people hold and how they came to hold them. We might call such facts “descriptive facts about morality”. (Let’s not call them “moral facts”.) Though some of those facts may be matters of controversy, the central controversy in discussions of whether morality is “objective”, is not over those descriptive facts, but over what kind of truth status moral claims have, and what (if anything) makes them true. (This is the subject of “metaethics”.) When I use those terms, I’m not including descriptive claims, about what moral values people hold and why. To illustrate what I mean by a moral claim, I mentioned two types that are among the most unambiguous: “Action X is morally wrong” and “You have a moral obligation to do Y”. Those are just representative examples. The class of moral claims is much broader than that.

In my last comment, I attempted to state my metaethical position clearly, but made no attempt to argue for it. If I’d wanted to argue for it, I would probably have made some claims of descriptive moral fact. But my goal was only to suggest that we can express our metaethical positions more clearly if we are careful to distinguish between descriptive questions about morality and questions about the truth status of moral claims. And I attempted to give an example of this by stating only my position on the latter question.

If a claim is true, then it expresses a fact. If a moral claim (e.g. “Murder is morally wrong”) is true, then it expresses a moral fact. That’s what I mean by a “moral fact”. I say that moral claims cannot be true, and so there are no moral facts.

I think I may have muddied the water and misled Coel by saying: “But [moral utterances] are also typically assertions of fact.” On one reading this may sound odd, since I’m also saying there are no such facts. What I meant was that a moral claim is an assertion as to a fact, an assertion of a supposed fact. It’s hard to find completely clear and unambiguous words here. If someone sincerely (but mistakenly) asserts that Mars is the third planet from the Sun, we might say that he is asserting a fact (or making an assertion of fact), but that he’s mistaken. It isn’t actually a fact. It seems to me that, when I say someone is asserting a fact (or making an assertion of fact), I only mean that he asserting what is a fact from his point of view. I’m not accepting that it actually is a fact. Do you see what I mean?

Perhaps, Coel, you think I could have made my meaning clearer by saying that someone who says “Murder is morally wrong” is mistaken in thinking that he is asserting a fact. But that would not have made my meaning clear. He is not mistaken in thinking that he’s making an assertion. He _is_ making an assertion. In that respect he is engaging in broadly the same kind of behaviour as someone who sincerely says, “Mars is the third planet from the Sun”.